In the early years of my running career, I simply went out the door and ran around the block or around the neighborhood, increasing the distance when I felt like it. It never occurred to me to run faster. Running farther seemed to be the goal.

A couple years later I joined a marathon training group, and we were split into groups based on our pace. There were no GPS watches, but I knew from my little Timex IRONMAN that it took me about 32 minutes to run around a certain number of blocks that I thought were about 3 miles, so I was assigned to the 11-minute mile group.

At that time, I’d never been introduced to the concept of effort. Both my weekday training runs and my Sunday long run with my group were not only run at the same average pace, but also with the same amount of effort. Oh, sure, while the increased effort in the later miles of the long runs was obvious, there were no sessions during which I pushed the effort on any of my runs, long or short.

This kind of “training” resulted in a few years of 5K races with finish times not much faster than my weekly casual runs. In my early to mid-30s, I was running slower than I do now at age 60 in every distance. I think we now call that our comfort zone.

Fast-forward about 20 years, when I received my first customized marathon training plan from McMillan Running. In every week of Greg McMillan’s plan for me, there were 2-3 easy or recovery runs. What threw me was this: “Run 40–50 [or 20–30, or 60–75] minutes”.

Okay, but how far? At what pace? Please explain!

Most runners are familiar with workouts based on a specific distance or, as in speed workouts, on hitting certain paces.

But what about running for a specified time, where instead of pace you are instructed to use effort as your goal? Many of us are so used to focusing on miles and paces when training that the concept of running for 40 minutes or at a certain effort level requires a little mindset adjustment. But the benefits of using a variety of ways to measure your workouts can make it worth the effort! (See what I did there?)

So then what are the benefits of time-based training runs? And how and when is running by effort an advantage over hitting a pace?

Time-based workouts

If you’ve brushed by a running magazine in the past few years, you’re probably familiar with this rule: make your easy runs easy, so you can make your hard runs HARD. Problem is, a lot of us don’t realize that what we call our “easy” pace is faster than what our heart rate would indicate to be easy.

The strategy behind time-based workouts (thank you, Greg McMillan!) is to get you on your feet for the full number of prescribed minutes. If the plan instructed you to run 4 or 5 miles instead of 40–50 minutes, your thought process might be something like this: “Let’s see. If I run 4 miles at my 5K pace, I’ll have enough time to watch The Bachelor before bed!” You’ll then end up racing when you’re supposed to be on an easy run, missing the benefit of recovery.

Instead, knowing you must stay out there for a minimum of 40 minutes is your permission to slow down, gain time on your feet and capture some “active recovery” time. Rather than being a slave to Garmin or Strava or Run the Year charts, let your body and your long-term goals be your master.

Benefits of time-based workouts include:

- Not hurrying through the workout forces us to give our body “active recovery” time.

- Taking time for slower workouts results in increased capacity of our aerobic system (i.e. endurance) with less chance of injury or overexertion.

- Mindful running tip: easy, time-based running creates opportunities to make eye contact, notice small things you pass every day, and spend more time outside.

- Use time-based easy runs to consider your stride, your gait, how your shoes feel, your arm swing.

Effort, or rate of perceived exertion (RPE)

As mentioned above, as a beginning runner I was unaware of relative effort scales or levels; for me, everything seemed to fall into the “very difficult” category of effort. So one of my first big breakthroughs came when I learned of the Borg scale to measure effort.

If you are familiar with using an effort number or level to determine the intensity of your workout, you may know about the Borg scale or perceived exertion scale. Even many fitness watches now include effort scale as part of their available feedback.

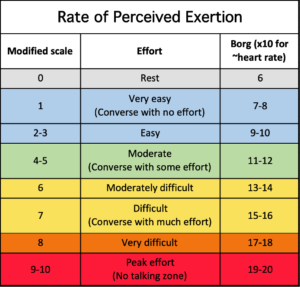

The Borg scale (Rate of Perceived Exertion, or RPE) was created by Gunnar Borg as a quick way to estimate heart rate as it related to intensity levels. His scale ranged from 6 to 20 so that by multiplying the effort number by 10, it indicated heart rate. For example, an effort level of 9 to 10, or very light exertion would translate to a heart rate of 90 to 100.

These days most runners use a more intuitive, modified perceived effort scale of 1-10, although the descriptions of Borg’s RPE scale and perceived effort are similar.

Because the chart takes your fitness level into account, the numbers are relative; what may be a 9–10 level of effort to me could be a 7 for a more fit athlete; therefore, you can rely on this to measure how hard YOU feel you are working. Similarly, if using the Borg scale and applying it to heart rate, what may elevate your heart rate to 145 beats per minute (bpm) may push mine up to 170.

Your heart rate monitor and other tools available on many GPS devices can help familiarize you with what the numbers mean to you in real life and real time.

Why use perceived exertion or effort to gauge your workouts?

Author Matt Fitzgerald has a fascinating and extremely useful explanation of other ways our perception of effort helps and hinders us in his book, How Bad Do You Want It?.

We can all agree, as Fitzgerald notes, that the perception of one mile is very different when you are instructed by a coach to go run one mile than when you are at mile 25 of a marathon and know you have to run one MORE mile.

But the most helpful and eye-opening concept Fitzgerald shares is the way we can shape our perception to our benefit: Knowing that a workout or race will be hard can create an acceptance that somehow makes the difficulty more manageable. Rather than being caught off guard when things get really tough, the expectation of discomfort or struggle during intense workouts takes a little of the fear away from striving for a new goal.

Consider these examples:

When asked to run 400m at 5K effort in training, our mind automatically classifies this repeat as “hard”. The same 400m repeat run at 10K effort sounds easier, because most runners will adjust their effort when running a 10K; it is twice as long, and we know we cannot sustain the same effort (or pace) that is possible during a 5K run. Therefore, less physical exertion is needed for a slower pace, and mentally we can feel more empowered to get out there and meet the goal pace. But if we are at the start line of a 10K race, the effort we know we must put into a good finish will suddenly become “hard.”

Similarly, a hill workout might instruct you to “run 6 to 8 times up a moderately sloped hill for 60–90 seconds at 5K effort; use the jog back downhill as recovery”. As you can imagine, running a true 5K pace for this workout could result in a disappointing result at best and possibly cut the workout short. The effort you perceive your 5K pace to be, on the other hand, should be the effort exerted to run up the hill, and your actual pace is (probably) not going to be the same as it would be if you were on a track or otherwise flat course. The benefits, however, are similar, and if you track your heart rate you’d probably see the correlation.

Developing this awareness of perceived effort takes some practice and mindfulness but will pay off both physically and in motivation.

Benefits to being aware of our own RPE include:

- Being mentally prepared for things to be harder. Or easier. And letting that mental fortitude push us through.

- Using effort instead of pace for very short intervals or fartleks of 15 to 30 seconds is vital, as your GPS will not adjust quickly enough to accurately gauge your pace.

- Our ability to withstand an increase in effort creates a change in perception of what is hard, medium, and easy, and this ultimately results in lower perceived effort. This is a fundamental benefit of training: if we are willing to tolerate harder workouts, our perceived maximum effort increases over time which in turn gives us more motivation to continue.

- Did you sleep poorly? Fuel poorly? Are you at the start or end of a workout or race? RPE changes may be based on our environment and current situation rather than lack of motivation or desire.

- When faced with wind, humidity or hills, where our slower pace reflects those hindrances, understanding RPE reduces any potential discouragement; stats on a graph do not paint the full picture of what a workout felt like!

Upgrading your training toolbox

Using time-based workouts in the manner they are intended should result in healthier running through the benefits of recovery. Using perceived effort as another method to measure your training will help you recognize how your heart rate and mental state affect your pace, endurance and even satisfaction in your training.

Add time-based and effort-based workouts to your training toolbox for mental and physical advantages, for variety, for a well-balanced fitness plan, and to recognize what might and might not be working.

If you are new to either of these training concepts, come back after giving them a go for a few weeks and leave a comment on what you discover. Do your workouts benefit from these additional measurement methods? Are you happier on a recovery run, knowing you can go run for 40 minutes as you like with no mandatory goal? Does focusing on varying effort levels open your eyes to what you can really accomplish at any given time or in any given situation?

I’m interested!

Want to receive Coach Bette’s monthly column in your Inbox? Be sure to subscribe to our newsletter or sign up as a RaceRaves member (it’s free)! And read her most recent column here.

About our columnist:

Bette Hagerty decided to run a 5K in 1992 after a few months of running around her neighborhood, using her car’s odometer to measure distances. When she found herself among a few hundred people talking about running, she knew she had found her community. Since then she has run several hundred races, from 5K to marathon distance and helped form two running groups.

Bette Hagerty decided to run a 5K in 1992 after a few months of running around her neighborhood, using her car’s odometer to measure distances. When she found herself among a few hundred people talking about running, she knew she had found her community. Since then she has run several hundred races, from 5K to marathon distance and helped form two running groups.

Bette is an RRCA Certified Running Coach and posts weekly Tuesday workouts on instagram as @BetteRunning. Her passions for running and writing have finally run into each other, and she looks forward to sharing her experiences and knowledge. She welcomes your glowing compliments at [email protected].

Other RaceRaves articles you’ll enjoy (trust us!):

Tested & Trusted Race Day Tips

Runners Choice: Best Marathons in the U.S.

Introducing your (smart) 50 States Map

Packing for a destination race

Best Bets for Boston Marathon Qualifying Races

Running on all seven continents

And for more helpful articles, check out our blog!

Find this article informative? Please share it, and let others know RaceRaves is the premier online resource to DISCOVER, REVIEW & TRACK all their races and to CONNECT with other runners!

Thanks, Coach Bette. Beautifully written, logically explained, and practically useful training advice.